Ever wonder why dollar coins never caught on in the United States, despite multiple redesigns and reissues? From the Eisenhower dollars to the Susan B. Anthony, the Sacagawea golden dollars, and even the Presidential coin series—each rollout was met with some initial curiosity… and then apathy. At this point, the mint flat-out says dollar coins are only for collectors and not for the general public.

It's not because coins are inconvenient. In fact, most developed countries rely far more heavily on coins for small denominations. Japan, Canada, the EU—all use coins for what we'd put on paper. Coins save money as well. Banknotes wear out and have to be replaced much more often than coins.

So what gives?

One often overlooked reason lies in how fragmented the U.S. currency system is.

You might think the U.S. Mint and the folks printing banknotes are the same people. I did. Most people probably do. We kind of assume this is how it is because that logically makes sense. But they aren't.

The U.S. Mint, part of the Treasury Department, is responsible for making coins. Paper money, however, is made by a different agency entirely: the Bureau of Engraving and Printing (also under the Treasury). But here's the kicker—neither of them decides what actually gets used. That's up to the Federal Reserve, a totally separate entity that orders and distributes the currency.

Here's where the tension begins:

- The Mint would love for Americans to use more coins. As mentioned above, coins last decades longer than paper notes, and once distributed, they're effectively little profit machines. - The Mint is staffed not just by fellow numismatics nerds like us, but also by people who genuinely want to save the government money.

- But the Federal Reserve—which buys coins and notes from the Mint and the Bureau—generally just orders whatever meets demand. And the demand for coins is… low.

Why? Well, you all know why. People prefer paper money. It's familiar, light, and fairly convenient. These days vending machines all take banknotes, so that standard of coin convenience has been erased. Sure, banknotes may wear out faster, sure, costing the government more money, but the people care little about that detail: for us they're easier to stuff in your wallet.

This isn't just an American quirk. In other countries too, the banknote is also always preferred. This is why, when a government wants to introduce a higher value coin, at the same time they remove the banknote for that value from circulation, thereby forcing people to use the coin. Canada did that. The EU did it. Japan has done it many times. I've written many posts on here looking at banknotes in Japan that long ago disappeared because they switched to a coin for that value.

That doesn't work in the US, though. When the US government tried to phase in dollar coins, the mint was only too happy to oblige. But the Bureau disagreed, fought against removing the dollar banknote, and won. The Mint and Bureau—separate agencies with different incentives—couldn't agree. And in a structure where agencies can protect their own turf, the result is predictable: gridlock.

This isn't just quirky government inefficiency—it's expensive. The Government Accountability Office (GAO) has repeatedly found that switching to coins could save billions over time. But... well, you guys know how it goes: without a unified policy or willingness to retire the $1 bill, the status quo wins.

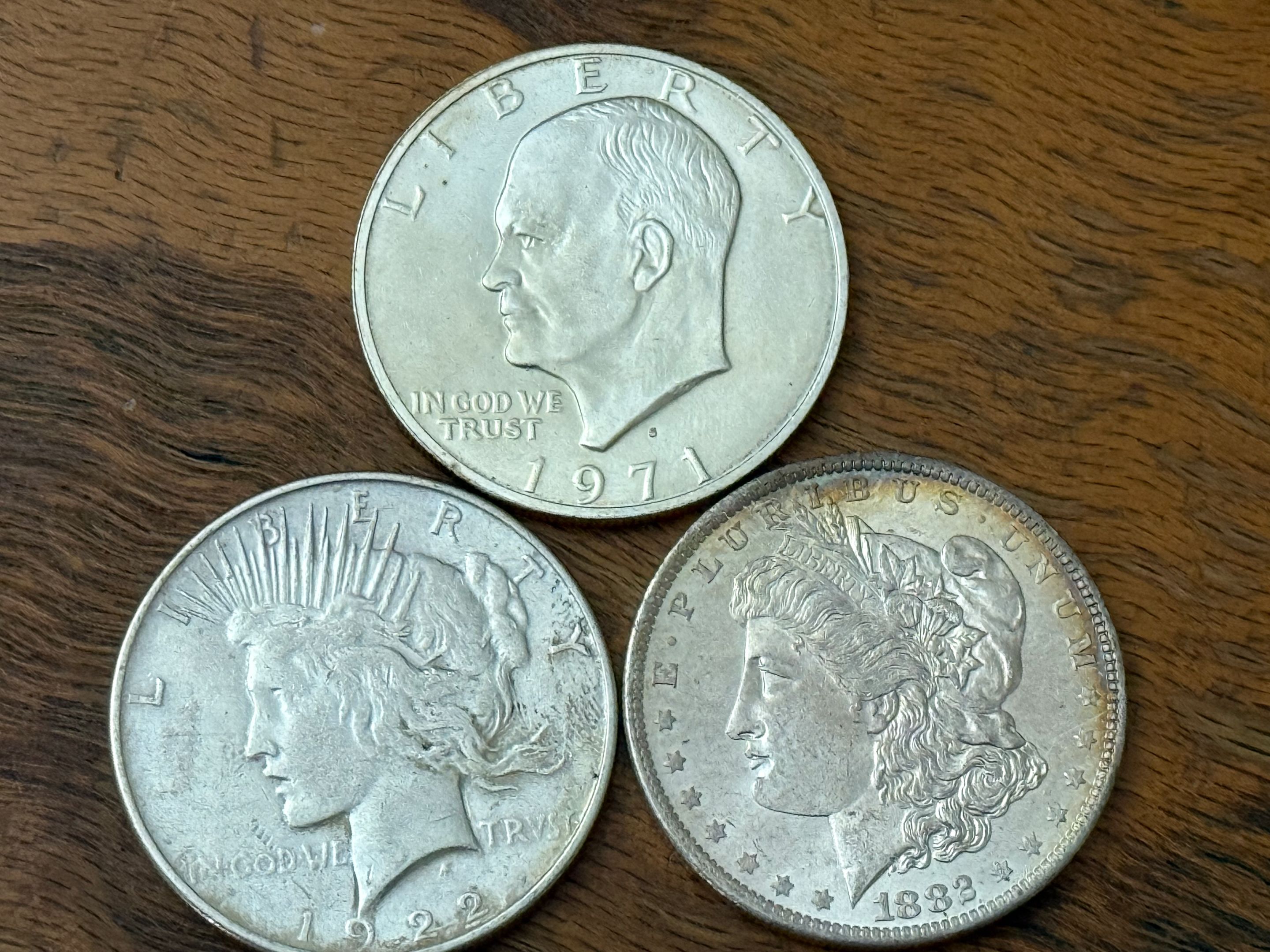

Meanwhile, the Mint keeps designing new dollar coins that few people ever see outside of collectors' albums or the occasional change from a vending machine. They're still minted. Still shiny. Still unused.

As always when I bring this issue up, I know it doesn't really matter. With a debit or credit card in everyone's pocket, few use any cash these days, banknote or coin. I just like the theoretical exercise of thinking about this stuff I guess.

❦